There are estimated to be close to 18,000 wolves living wild in Europe and in many areas their numbers are growing – but a controversial referendum in Switzerland this weekend could cement a law that would see the predator’s numbers being more tightly controlled by shooting.

Do such conflicts mean the wolf is less likely to be reintroduced closer to home in countries such as Scotland and Ireland?

From fairytale villain to a shepherd’s worst nightmare, the wolf has always had a bad press – but after being hunted to near extinction across much of Europe, their numbers are growing again.

The most recent estimates of Europe’s wolf population are from 2016 and put it at close to 18,000 with up to 16,000 of these living in the EU.

Wolf numbers are growing in countries including Italy, France, Germany and Poland, but in Ireland the wolf has not been seen in the wild since 1786, when the last one was killed in County Carlow.

The Swiss Referendum: What’s at stake

In Switzerland there are estimated to be around 100 wolves in 11 packs, with some lone wolves, according to the publicly-funded Swiss wolf monitoring organisation KORA.

This Sunday the government is urging close to 5.4 million of its citizens to decide in a referendum whether the animal’s protected status should be partially downgraded, giving local governments or cantons more power to control the wolf population.

The Swiss government said the current hunting law dates back to 1986 – almost a full decade before the wolf was reintroduced in Switzerland.

The first pack formed in 2012 and since then the population has been growing steadily. Some of the wolves are collectively being held responsible for the deaths of between 300 and 500 sheep and goats each year, although many more of these die in accidents caused by falls, weather and roads.

Last year Swiss farmer Martin Keller lost 59 sheep to wolf attacks. He lives near a wild stretch of the Rhine River, near the mountain village of Ilanz, where he also raises goats.

This year, he installed €23,000 euro worth of electrical fencing. His livestock went unscathed this summer, but he says his farm’s finances suffered: “The law’s opponents always talk about a ‘shoot-to-kill’ initiative,” said Keller.

“We don’t want to kill all the wolves. All we want is to be allowed to regulate problem wolves, and that local decisions can be made more easily.”

The government argues that even animals protected by fencing and dogs have been attacked as wolves learn to circumvent these measures.

However, groups associated with nature conservation have banded together with Green and left-wing political parties to gather enough signatures for a referendum that could halt the change in the law.

Some 87% of livestock killed by the wolves were unprotected, according to one Swiss canton’s tally, and pro-wolf groups argue that the Swiss farmers, who are heavily-subsidised, should deploy more fences, shepherds and herd dogs instead of resorting to guns.

“I think that throughout history, the wolf has always had bad press,” said Karel Ziehli, from the Institute of Political Science at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

“Just think of children’s stories where the wolf is always portrayed as dangerous, a predator to humans….However, scientific studies on the increase in wolf populations in Europe over the last thirty years seem to indicate there have never yet been any cases of wolves that have killed a human being.”

Mr Ziehli, who specialises in agriculture, hunting and forest policies, is also a member of the Green party which opposes the changes to the hunting laws.

However, he admitted that as wolf numbers have grown, they have been causing more problems, particularly in mountainous areas of Switzerland where each year more wolf cubs are reported:

“This evolution will continue at an estimated rate of 20 to 30 per cent more animals per year,” he said.

“Today, the wolf is posing problems that have not been known since its eradication at the end of the 19th century. They kill between 300 to 500 sheep and goats per year (out of a total of about 200,000 sheep), which represents only 6% of sheep deaths, as argued by wolf protectors.

“But wolves also have indirect effects on other aspects. Indeed, in some regions where there is a presence of this predator, the cows and dogs that are on the mountain pastures are under stress, making them more aggressive towards hikers walking in the Alps. This can therefore have an impact on tourism.

“The authorities therefore want to be able to better regulate this species protected by the Bern Convention, in order to have a better cohabitation with human beings. They also want the wolf to maintain its fear of humans.”

Susan Misicka, a journalist with SWI swissinfo.ch, the international branch of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, said wolves that cause problems by killing and maiming sheep can already be controlled in limited circumstances.

The new law would make it so that animals can be shot preventatively, even if they haven’t actually attacked livestock.

But if the government wins this referendum, it will be easier for authorities to control wolf populations at a local level.

“For the parliamentarians who adapted the law, the idea was to have a way of regulating the wolf population more quickly. Right now it is already possible to regulate the wolf population if an individual animal kills 25 sheep, within a month, then that animal can be shot, but you need Federal approval.

“The new law would make it so that animals can be shot preventatively, even if they haven’t actually attacked livestock… and mountain farmers are happy about this because that way they can do something before any farm animals are killed.”

She expects this referendum to be a closely fought one. The result is expected to be known by Sunday evening and recent polls commissioned by the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation suggest the vote could go either way.

“It’s really close, its probably too close to call. The ‘No’ vote, rejecting the changes to the hunting law, they were a little bit ahead but again its too close to call and we won’t know ’til Sunday.”

The referendum was originally due to be held in May this year but was postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Voters in Switzerland can always send in their ballots by post, but even more people are being urged to do this year.

She says the debate around wolves has captured the public imagination and is a very emotive issue.

“There’s been a lot of excitement and fear over the increase in the number of wolves. I think also people have been appreciating nature more with the pandemic and getting outdoors more.

“So I think there’s a struggle between the people who live in mountainous areas and have livestock and also people who don’t get to go out in nature as often and for them the idea that biodiversity could be reduced more easily is upsetting to them.

“But in either case hardly anybody actually sees a wolf, because they are so shy.”

Mr Ziehli said he expects the vote to be split along geographical divides.

“This vote might show a cleavage between mountain regions, marked by the presence of the wolf, and cities. In Switzerland, the largest cities are predominantly left-wing and ecologically oriented and therefore have a political position in favour of protecting the wolf.

“In the mountain cantons, the wolf is much more present in people’s daily lives and does not enjoy a good image, as they kill the sheep and goats of shepherds who generally have difficulty surviving. This leads to a rather divisive debate between people living in the cities and those living in the mountains.”

The wolf and the EU

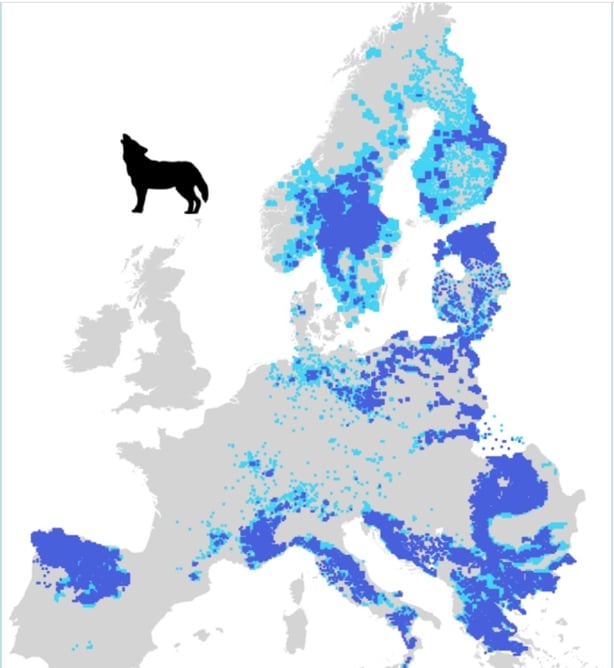

After bears, wolves are the second most common large carnivore in Europe. The wolf is protected across the EU under the Habitats Directive of 1992 as an ‘Annex V’ species which means its removal or exploitation in the wild can only happen in limited circumstances, which must not threaten its conservation status.

The highest number of wolves in Europe are in the Carpathian mountains and along the Italian Peninsula, but their numbers have been growing recently in central European countries like Germany, where the predator has again been brought into conflict with farmers.

Most German states have now established wolf management plans that include support for farmers through financial compensation for livestock damage and also the funding of preventive measures such as electric fencing and dog patrol.

Last year German federal authorities counted 105 packs of wolves, 29 pairs and 11 territorial individuals.

In the same year, across Germany there were reports of more than 2,800 cases of killed, wounded or missing livestock, mostly sheep.

“As the wolf occurrence increases, the damages caused by wolves increase as well,” says Corinne Bertz, is a spokesperson for the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation which works to help wolves and humans co-exist.

“Most wolf attacks on livestock are recorded in areas where wolves are establishing new territories and sheep and goat keepers are not prepared yet for the presence of wolves. Mostly, damages decrease within one or two years when animal keepers are properly equipped to handle wolf presence.”

Most German states have now established wolf management plans that include support for farmers through financial compensation for livestock damage and also the funding of preventive measures such as electric fencing and dog patrol.

But now Germany is at the centre of a test case that has been referred to the European Commission, following changes the German government made this March to the Federal Nature Conservation Act.

Under this legislation, the wolf remains a protected species, but regional governments can now decide to shoot wolves attacking livestock, in circumstances where it can be shown that there have been two wolf attacks on livestock in an area that had been properly protected.

Initially, only one individual in a wolf pack can be shot and if the attacks stop, then no other individual can be shot.

The European Commission received a number of complaints about the new law, which claim it does not comply with the EU Habitats Directive. An investigation has been launched and the Commission is now assessing the information it has received from German authorities.

Brigitte Sommer of the wolf protection group Wolfsschutz Deutschland, which protested over the new law, says she will be monitoring the case closely.

“The Bill was pushed through by the Federal Government at the beginning of the year against expert opinions and means in Germany wolves can now be shot more easily. I believe the hunter and farmer lobby is gaining more and more power and becoming stronger and stronger throughout Europe,” she says.

A comeback in Scotland and Ireland

Whilst the wolf has re-established itself naturally in much of mainland Europe, even those who would like to see it living in the wild again here in Ireland and in Scotland, see little prospect of this happening successfully in the short-term.

Killian McLaughlin from Wild Ireland has a pack of three wolves which have been living in an enclosed sanctuary in Burnfoot, Co Donegal since last year. He also cares for abused brown bears.

He has featured on RTÉ’s Mooney Goes Wild on Radio One as well as a documentary shown recently on RTÉ One called Return of the Wild: The Bearman of Buncrana.

Mr McLaughlin said his wolves are three males. “Two of them are brothers, one is unrelated but he’s just one day older than the other two.

“I put them together when they were really young and created what’s called a bachelor pack. It would happen in the wild where young males would leave their family pack and go off together until they found a mate of their own to start their own pack.”

He said his wolves are fed meat, rather than live prey and are not allowed to roam beyond Wild Ireland’s fences.

“As much as I would love to let them out into the wild again, they do live in a fenced enclosure in the forest and they don’t have to hunt for themselves.”

He said the wolf was once revered in Ireland and he hopes that the recent pandemic means people are finding a new respect for nature.

“The topic of re-wilding is really important. I think all of us need to realise that we are not separate to nature, we are a part of nature as well.

“Before the wolf went extinct in Ireland the Irish people had a huge respect for their predators. They called them Mac Tíre which means son of the land and that was like a term of loyalty and they were respected as such.”

Mr McLaughlin said it was only when Oliver Cromwell came to Ireland that a bounty was put on the wolf’s head and professional hunters from elsewhere in Europe moved in to hunt the wolf to extinction here.

“The last wolf was hunted into extinction in Co Carlow at the foot of Mount Leinster by a guy called John Watson and as far as we know that was the last of their kind.”

The wolf has been successfully reintroduced in Yellowstone National Park in the US in 1995, but Killlian does not believe the same thing could happen easily somewhere like Donegal where there is much less land with roads and farmers in closer proximity.

“You also have to make sure that the reason that they went extinct is no longer there. So in our case, hunting is the reason we exterminated the wolves and unfortunately that’s still here. You only have to look at the Golden Eagle programme here in Donegal.

“It went extinct about a hundred years ago and they were re-introduced at Glenveagh National Park, right here in Donegal and it’s really sad to see the Golden Eagle is now in danger of going extinct here again for the second time.

“That’s heartbreaking and its embarrassing so that attitude of hunting and exterminating predators has not gone away.”

The return of the wolf has been discussed as a more realistic prospect in Scotland, where there is more space and big problem caused by the overgrazing of deer.

“There is certainly a major deer problem in the UK (and presumably in Ireland) basically because we have no apex predators any more, other than us!,” said Jon Davies, director of the British-based consultancy group RSK Wilding.

“This is having significant effects on our ecology, as woodlands, in particular, are becoming over-grazed. Given the difficult relationship between wolves and farmers, as evidenced by the Swiss debate, that does not mean that wolves are the answer in most locations.”

However, he said that where there is sufficient space to roam and where there is a low risk of negative interaction with sheep farming “then there is no reason why this couldn’t be done in the right place and under the right controls and conditions.

“This of course is why reintroductions are being considered in highland Scotland rather than lowland England!”

This re-introduction has been the long term dream of Paul Lister, founder and trustee of the European Nature Trust and ‘custodian’ of the 20,000 hectare Alladale estate, a fenced off wildlife reserve in the Scottish Highlands north of Inverness.

He has been fighting for years to return wolves to this area in a controlled way, which he likens to game reserves in South Africa.

“Wolves returning to the wild in Britain is a pipe dream,” he said, but he believes it can be done under the right conditions.

Unlike the wolf pack in Donegal, he said he is not interested in what he calls a “half-way-house” and would like the wolves on his estate to breed and hunt the red deer there.

At the age of 61, he said he is now working full time to allow wolves to live on his land and has established a team of young professionals specialising in biology, law and marketing to help him do this.

Mr Lister said it could bring a lot of lucrative tourism to the area, citing the example of the wolves of Yellowstone which are believed to have generated $40 million in additional revenue for the tourism there.

“My whole raison d’être is connecting people to nature,” he said.

“As for Switzerland as far as they are concerned, they should be delighted about having wolves coming back into their chocolate box country.

“Wolves have a part to play in the ecosystem and livestock do not. We have to find a way to work with animals and not against them.”

Source: https://www.rte.ie/news/world/2020/0925/1167565-wolves-europe/