by Catherine Kozak

Even with a federal judge’s recent ruling in favor of conservation of red wolves in northeastern North Carolina, uncertainty remains whether reinvigorated management of the endangered species would be able to reverse course to save the world’s only wild population of the species – or whether the conditions exist to even try.

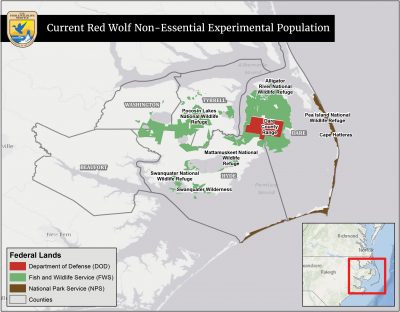

Only two or three dozen red wolves still roam the swampy forests and farmland within the 1.7 million-acre recovery area in Hyde, Tyrrell, Dare, Beaufort and Washington counties, down from the peak in 2006 of about 130. About 200 wolves also live in captivity.

In the Nov. 5 decision, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina Chief Judge Terrence W. Boyle declared the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service violated multiple provisions of the Endangered Species Act by discontinuing successful management tactics that controlled coyote hybridization and integrated captive wolf pups into the wild population.

Boyle also ordered a permanent ban on the capture and killing of red wolves on private property without proof that people, pets or livestock were endangered.

It was a clear victory for the plaintiffs, the Red Wolf Coalition, Defenders of Wildlife and the Animal Welfare Institute, at least for now. But the wolves’ future in the wilds of North Carolina will hinge on how Boyle’s decree is reflected in Fish and Wildlife’s final management rule, which was expected to be published by Nov. 30.

Inquiries to the agency seeking information about the impact of the ruling were referred to the U.S. Department of Justice, which did not respond to emailed questions.

The ruling stated that there no impediment for the court providing relief to plaintiffs “pending publication of a final rule.”

Released this summer, the “Proposed Revision of the 10(j) Rule for the Nonessential Experimental Population of Red Wolves in North Carolina” would dramatically downsize the wolves’ range to land in Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge and the Dare County Bombing Range in Dare and Hyde counties. Animals that strayed beyond that protected area could be killed. About two packs – 10 to 15 wolves – are estimated to currently live in the proposed range. Also, the proposed final rule would not restore coyote controls or release more captive-born wolves into the wild population.

“The proposed rule will not in any way remedy the legal violations,” said Sierra Weaver, senior attorney in Chapel Hill for the Southern Environmental Law Center, or SELC, which represents the plaintiffs. “You can’t simply take away these management measures.”

Weaver said much of the rule-making process was done “behind closed doors,” so she said it is not surprising that the agency has not communicated about its response. As of this publication, the law center had not heard from Fish and Wildlife.

“What the agency is going to do is up to the agency,” she said. “To comply with the judge’s ruling, they’re going to have to go back to … those measures that they know had worked.”

D.J. Schubert, wildlife biologist with the Animal Welfare Institute, said it is a “bit of a waiting game” to see what the final rule will be when Fish and Wildlife finally puts it out, but the mandate in the Boyle’s ruling is not in doubt.

“It’s black and white on paper that a federal court has said (to) a federal agency . . . ‘What you’re doing is wrong and you have to fix it ’,” Schubert said. “The Fish and Wildlife Service knows what the tools are, so it’s not some mystery. They know what to do – it’s just a matter of them doing it.”

Local Opposition

Red wolves once roamed vast swaths of the southeastern U.S., but by the 1960s, predator controls, habitat loss and overhunting left the population decimated. Listed as endangered in 1967, the species was declared extinct in the wild in 1980. Some surviving wolves captured along the Gulf Coast were successfully bred in captivity for 10 years.

In 1987, four pairs of pups were released in the Alligator River refuge, and within five years, there were about 30 wolves. At some point along the way, the recovery area was expanded to its current 1.7 million acres, encompassing public and private land in five counties. Before long, much to the surprise – and resentment – of farmers and other landowners, red wolves started wandering onto their property.

That was when the agency’s relationship with the community started to sour.

“Who gave the Feds the right to spread an endangered species throughout those 1.7 million acres of private or state ownership?” Wilson Daughtry, owner of Alligator River Growers and part-owner of Lux Farms, both in Engelhard, asked in a recent email.

Boyle’s ruling, Daughtry said, appears to have “given the pro-wolf advocacy groups the green light to try and force these animals upon the private landowners again, by applying pressure to FWS through his ruling.” And that, he added, “is a classic taking of private land for public use without just compensation.”

The problem is not so much that a wild predator is trespassing on their land – bear and fox are also prolific in the region – it’s that the landowner can’t do anything about it, he said. Red wolves are protected under the Endangered Species Act, which is administered by Fish and Wildlife, and it is unlawful to kill them.

From Daughtry’s telling, it seems as if the program may have gotten off on the wrong foot soon after it started. Recounting an incident where a Hyde County landowner was arrested for shooting a red wolf that was in his pasture with his cows, he said the man was charged with a federal crime. Part of his penalty, in addition to a fine, he added, was cleaning the wolf pens.

“That guy thought he was going to serve some serious time for what he did,” Daughtry said. “How do you think he, his family and his community now feel about the Red Wolf program?”

Without compensation, no landowner that he knows in the recovery area would back the program, Daughtry said. On the contrary, he said, people feel as if the agency is “shoving the wolves down our throats” and that the agency misled them and can’t be trusted.

Tyrrell County landowner Jett Ferebee took the helm about six years ago for other landowners in the recovery area who oppose the red wolf program. Since then, he has been a vocal advocate for elimination of the program, and has succeeded in getting attention and support from state and federal public officials. Ferebee has contended in numerous published letters and comments that the red wolf is really just a coyote hybrid and undeserving of protection, and that the recovery program is a failure and a waste of taxpayers’ money. The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission also contends that coyote inbreeding has doomed the recovery program.

But intentional killings by gunshot and poisoning may have been more of a threat to the wolf, with incidences increasing over the years. Some of the shootings were the result of mistaken identity, with the shooters confusing the wolves for coyotes.

When the recovery program was going full steam in the 2000s – the program’s goal initially had been 220 wolves in the wild – biologists were having wonderful luck with mother wolves accepting captive wolf pups, sprinkled with a little urine from a wild pup, that were added to dens when she left to hunt. Many wolves were fitted with tracking collars, and the number of packs, dens and births every year were counted and monitored by a recovery team based at the Alligator River refuge.

Another very successful management technique to limit coyote hybridization involved capturing and sterilizing coyotes, and then returning them to where they were captured. The coyote instinctively would hold the territory, in the process keeping out fertile coyotes. As the law of the jungle – or forest – would have it, a bigger wolf would eventually show up, dispatch the coyote, and move in.

But when more wolves were killed, whether by vehicle strikes or gunshots, it disrupted the balance, allowing fertile coyotes to slip back through holes created by absent wolves. Furthermore, the deaths would sometimes remove half of a mating pair, or a mother caring for pups, negatively affecting their reproduction.

By 2012, Fish and Wildlife, responding to decreased political and community support, started scaling back the program, and eventually eliminated much of the active management, including pup fostering and coyote sterilization.

Schubert said that, despite the antipathy from some landowners, many have been very supportive of the red wolf recovery program. Still, successful management efforts have to include working together with landowners and hunters, she said. “Fish and Wildlife has learned over the year that engaging with the local community is critical,” she said. “I hope they would reconsider how they view the red wolf and not view the red wolf as an enemy … They can be part of a conservation success story.”

Additional habitat also must be found for the red wolf, otherwise the species recovery range is in danger of going from “one to none,” Schubert explained. “It’s really risky to have a single recovery area.”

The Endangered Species Act, “one of the strongest and best laws in the world” for recovery of species, Schubert said, operates with an understanding that the act wouldn’t be capable of recovery of every species only on federal land. “It really requires buy-in and cooperation from private landowners,” she said.

The best science is supposed to dictate management, Schubert said, but it doesn’t mean landowners’ rights can be ignored. They should be kept informed of management actions. At the same time, she said, landowners also have responsibilities to participate in the rule-making process.

“But the reality is, if we are to protect the amazing diversity we have in North American, that includes uses of the land to protect endangered species. It just requires more effort to make sure you get the required permits.”

An analysis by Wildlands Network provided in a Nov. 1 press release found that nearly 99 percent of the more than 108,000 comments on the proposed rule submitted to Fish and Wildlife supported strong federal protections for red wolves. The same percentage of support was evident in comments submitted just by North Carolinians, and by nearly 80 percent of comments submitted by those living in the five-county recovery area.

Gov. Roy Cooper also expressed support for the recovery program in a comment submitted to the wildlife service.

‘Dastardly Acts’

Ron Sutherland, conservation scientist with Wildlands Network, said that in light of Boyle’s stern rebuke of Fish and Wildlife, it would great if the agency went back to its prior adaptive management strategies. At least, he is hoping that the ruling will result in more oversight over the agency’s management of the red wolves.

“It makes me feel good inside that the federal agency is not getting away with violating the spirit of the Endangered Species Act,” he said. “There were so many dastardly acts that were done in the last three or four years.”

Sutherland said that the wolves have been blamed unfairly by hunters for decreases in deer populations.

Since 2015, he has led an effort by Wildlands Network to photograph wildlife in northeastern North Carolina using motion-detection cameras with infrared light for night shots. Thousands of photographs, posted on the photo-sharing site Flickr, show wolves, coyote, bear, deer, fox and various other wild animals going about their business. It also showed, Sutherland pointed out, that there are plenty of deer.

Recent photographs, he said, captured groups of two or three wolves in the Alligator River refuge.

In July, the group hired a woman to conduct outreach in the community, Sutherland said. One project they’re planning is to partner with landowners to install motion-detection cameras on their property.

Sutherland said he is “cautiously optimistic” that Fish and Wildlife will do more to help the red wolves and that the recovery effort can turn the corner.

Whatever the agency’s response turns out to be, Weaver said that community outreach by Wildlands Network and the Southern Environmental Law Center’s clients could go far in restoring “peaceful co-existence” with wild red wolves.

“What we know is that the public overwhelmingly supports red wolf conservation,” she said. “There has been a very, very small number of incidences with these animals … that’s all a red herring.”