Jason G. Goldman

Chester Starr of the Heiltsuk First Nation knows that the wolves of British Columbia come in two varieties: timber wolves on the mainland and coastal wolves on the islands. Genetic research has finally confirmed what Starr’s tribe has always known.

It was Starr’s “traditional ecological knowledge” that initially inspired Polish Academy of Sciences researcher Astrid V. Stronen and University of Calgary scientist Erin Navid to take a closer look at British Columbia’s wolves. They wanted to see whether the Heiltsuk Nation’s folk knowledge was reflected in the wolves’ genes.

The puzzling thing is that wolves are capable of moving over vast geographical distances. They can easily travel more than 70 kilometers per day without even breaking a sweat. They can cross valleys and mountains, and can swim across rivers and even small channels of sea. Yet Stronen, Navid, and colleagues found stark genetic distinctions among wolf groups in an area just 2000 square kilometers.

Why are there such clear genetic groupings among wolf groups who ought to be able to intermix?

According to the researchers, it’s all about what they eat. Despite the tiny distances between the mainland and the islands – sometimes less than 1500 meters of water – there are tremendous ecological distinctions. The mainland is rugged and is home to tons of wildlife, while the islands are less mountainous and host fewer species. On the mainland, grizzly bears compete with wolves, but on islands, wolves are the top dogs. On the mainland, wolves can feast on moose and mountain goats. On the islands, wolves rely on marine resources, like fish, for 85% of their diets.

Despite their ability to travel great distances, some animals’ behavior becomes so specialized, thanks to the environment into which they were born, that they wind up sticking close to home.

It’s an important reminder that nature and nurture, genetics and environment, are more tightly linked than it might seem at first. Chimpanzees and bonobos only diverged some three million years ago (our species last shared an ancestor with them around six million years ago), but today couldn’t be more different. As with the wolves of British Columbia, researchers think that the remarkable differences in chimpanzee and bonobo culture originate, at least in part, in their diets. Chimpanzees evolved in forests with fewer dietary resources than bonobos did. Fruits are a bit harder to come by for chimps, which may explain why they evolved to be more competitive. Bonobos, on the other hand, evolved in a land of plenty. The reduced competition over food may have led the so-called “hippie ape” towards greater tolerance and cooperation. Even small differences in diet and in foraging and hunting styles can have massive implications for the evolution of a group of animals.

The distinction between coastal and mainland wolves, in some ways, mirrors the distinction between polar and grizzly bears. It is thought that the two bear species diverged because polar bears evolved in regions where they relied on the sea to provide their food, while grizzly bears remained skilled at hunting on dry land. Like polar bears, those wolves who found their way to the islands have simply become skilled at fishing, causing them to remain in marine landscapes. Will the wolves of British Columbia follow in the footsteps of the bears, splitting into two different species? Only time will tell.

It doesn’t matter if an animal is physically capable of dispersing over large distances. Instead, what matters is whether they can thrive in environments distinct from the ones in which they learned to survive. Even one neighborhood over, a wolf that was a master fisherman might starve if faced with the task of taking down a massive moose.

Read the whole open-access paper at BMC Ecology.

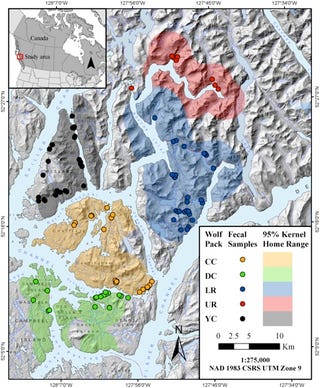

Photos: Chris Darimont; Guillaume Mazille. Used with permission. Map via Stronen et al.