Melissa Siegler, Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune

WISCONSIN RAPIDS – Recent wolf attacks in central Wisconsin have reignited feuds about the protection of wolves under the Endangered Species Act, which prohibits killing the animals unless human life is in danger.

Ray and Barb Calaway, farmers near Wisconsin Rapids, woke July 8 to find that 13 of their sheep had been killed by wolves. Three days later, Diane Schiller’s 18-year-old dog, Tucker, was killed by a wolf just a quarter mile from the Calaway’s farm.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced major changes to the Endangered Species Act on Monday. Changes to the law, which protects about 1,600species in the U.S. and its territories, include ending blanket protections for animals classified as threatened and allowing the federal government to consider the cost of protecting certain species.

The department proposed delisting wolves in March, saying the population has stabilized and is no longer in danger of extinction. Delisting the animals would also allow states to responsibly manage the population on their own, so the federal government can focus on other species still in need of conservation.

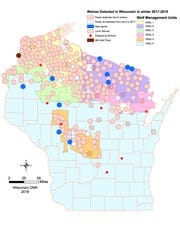

Wisconsin is one of about 12 states with a wild gray wolf population, according to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. The state had at least 914 wolves last winter with most of them concentrated in the northern portion of the state. The current data are consistent with those of the previous two years. Wisconsin saw its wolf population reach its highest point between 2016 and 2017 with 925 wolves roaming the state.

A map showing wolf packs identified in Wisconsin in the winter of 2017-18. The most recent work, conducted in 2018-19, showed a very similar distribution, according to the DNR, but with a few additional packs within known wolf range. The updated map is expected to be available later in 2019. (Photo: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

Though the population in Wisconsin has stabilized, that doesn’t mean it’s stabilized in other parts of the country, said Daniel Hirchert, a wildlife specialist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Hirchert said the conflict between wolves and farmers goes as far back as raising livestock does. The victims of documented wolf attacks range from livestock to hunting dogs to pets. Hirchert told USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin in July there is no history of humans being attacked by wolves in Wisconsin.

Before Wisconsin was settled in the 1830s, the DNR estimates, there were 3,000 to 5,000 wolves in the state. As more people moved to the state, farming their land and hunting animals wolves preyed on, the carnivores turned to livestock for easy meals. The population slowly depleted as the state placed bounties on wolves.

The animals didn’t receive federal protections until the Endangered Species Act was signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1974.

After a spike in the number of wolves in the 1990s, they were classified as “threatened” in 1999 with only 205 wolves in the state, according to the DNR. In 2004, they were reclassified as “protected.” The most recent protections were implemented in December 2014.

The protections have been a point of contention between farmers who want to protect their livestock and environmental groups and experts who want to preserve the wolf population.

For the Calaways, the attack on their farm meant they took a financial hit. The DNR reimburses people for the financial loss of livestock, but the couple said they weren’t sure if it would cover the full loss. Their family also had a wolf attack on their farm in 2017 that left two sheep dead.

They said in July they hoped wolves would be taken off the endangered list, so the population could be controlled. Ray said he would like to see the DNR have more power instead of the federal government.

“I don’t believe in just shooting and killing (the wolves), but when it comes to something like this, I think something needs to be done,” he said.

As of Wednesday, there have been 44 confirmed or probable wolf attacks in Wisconsin since the beginning of 2019, according to the DNR’s Wolf Depredation Reports, which tracked the following:

64 attacks in 2018;

52 attacks in 2017;

89 attacks in 2016;

77 attacks in 2015;

53 attacks in 2014; and

65 attacks in 2013.

Farmers can use many methods to deter wolves and other predators such as bears or coyotes. Bright lights, electric fencing and even other animals, such as llamas, are good ways to keep wolves away from livestock. But Hirchert of the USDA said it is always possible wolves will find a way around barriers.

2019 Wolf attacks in Wisconsin through August 2. (Photo: USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin)

“Nothing works forever, and (wolves) are always trying to get around abatement techniques,” he said. “As long as we have livestock and as long as we have carnivores, a carnivore is going to prey on that livestock.”

Now that most livestock have been “domesticated,” they aren’t as wary of potential predators that will see them as an easy meal, he said.

Melissa Smith, founder of the nonprofit Friends of the Wisconsin Wolf and a former wolf tracker, differed in her observation, saying wolves will leave livestock alone if effective abatement methods are used. The prey won’t be worth their trouble, she said.

Ultimately, farmers and landowners need to have some personal responsibility when it comes to protecting their own animals, Smith said. Using abatement options, such as strong fencing, lights and other animals, is more effective in protecting livestock than killing wolves, she said.

“When you don’t work with nature,” Smith said, “there are going to be more losses, and not just with wolves.”

Decreasing the wolf population could also have an adverse effect on the ecosystem, she said. The carcasses of the animals wolves kill decompose and provide nitrogen and other essential nutrients for the soil. Many other animals, including bald eagles, gray owls and bobcats, also rely on wolves to kill their meals, so they can scavenge the remains.

“Without wolves, the ecosystem goes haywire,” Smith said.